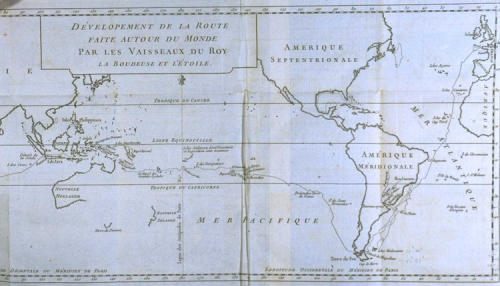

On the 12th of April 1769 Cook wrote: “and at 6 AM it (Tahiti) bore from SSW to WBN being little wind and calm several of the Natives came off to us in their Canoes, but more to look at us than any thing else we could not prevail with any of them to come on board – and some would not come near the ship”

On the 12th of April 1769 Cook wrote: “and at 6 AM it (Tahiti) bore from SSW to WBN being little wind and calm several of the Natives came off to us in their Canoes, but more to look at us than any thing else we could not prevail with any of them to come on board – and some would not come near the ship”

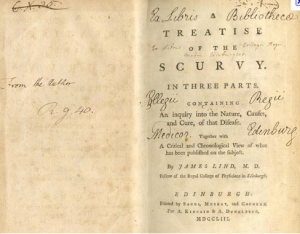

Despite the distance travelled, Cook and his crew arrive in good health. Thanks to an unusual combination of food and drink. So wrote Cook as he dropped anchor: “At this time we had but very few men upon the Sick list and these had but slite complaints, the Ships compney had in general been very healthy owing in a great measure to the Sour krout, Portable Soup and Malt…”.

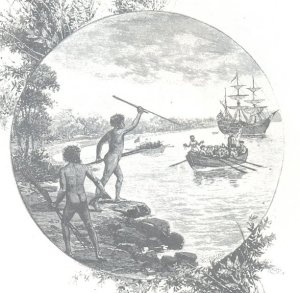

So with a full compliment of crew and civilians, Cook approached the island of Tahiti for the all-important observation of the Transit of Venus. Here we get a glimpse of an Englishman, in his own words, as he “meets the locals”….

And it appears to be exactly as we would like to imagine, an idyllic meeting on a blue ocean, surrounding a beautiful tropical island…

And it appears to be exactly as we would like to imagine, an idyllic meeting on a blue ocean, surrounding a beautiful tropical island…

“We had no sooner come to an Anchor in Royal Bay as before Mentioned than a great number of the natives in their canoes came off to the Ship and brought with them Cocoa-nuts, &ca and these they seem’d to set a great Value upon- amongest those that came off to the Ship was an elderly Man whose Name was is Owhaa, him the Gentlemen that had been here before in the Dolphin kne ow and had often spoke of him as one that had been of service to them, this man, / together with some others / I took on board / and made much of him thinking that he might on some occasion be of use to us”

The last comment indicates that Cook was there for a purpose (the Transit of Venus and future discovery for the Crown), not as an individual intent on “experiencing the color and nuances of a new culture”…

“1769 Friday Apl 14th This morning we had a great many canoes about the Ship, the Most of them came from the westward but brought nothing with them but a few Cocoa-nuts &Ca Two that appear’d to be Chiefs we had on board together with several others for it was a hard matter to keep them out of the Ship. As they clime like Munkeys, but it was still harder to keep them from Stealing but every thing that came within their reach, in this they are prodiges expert”

The ever logical Lieutenant Cook quickly apprised the situation, and realising their stay would not be short drafted a list of regulations for the behavior of his people. Namely…

“RULES to be observ’d by every person in or belonging to His Majestys Bark the Endevour, for the better establishing a regular and uniform Trade for Provisions, &c:a with the Inhabitants of Georges Island —

1 st To endeavour by every fair means to cultivate a friendship with the Natives and to treat them with all imaginable humanity —

2 d A proper person or persons will be appointed to trade with the Natives for all manner of Provisions, Fruit, and other productions of the earth; and no officer or Seaman or other person belonging to the Ship, excepting such as are so appointed, shall Trade or offer to Trade for any sort of Provisions, Fruit or other Productions of the earth, unless they have my leave so to do —

3 d Every person employ’d a shore on any duty what soever is strictly to attend to the same, and if by neglect he looseth any of his Arms or working tools, or suffers them to be stole, the full Value thereof will be charge’d againest his pay, according to the Custom of the Navy in such cases- and ^ he shall recive such farther punishment as the nature of the offence may deserve —

4 th The same penalty will be inflicted upon every person who is found to imbezzle, trade or offer to trade with any of the Ships ^ Stores of what nature so everunless they

5 th No Sort of Iron, or any thing that is made of Iron, or any sort of Cloth or other usefull or necessary articles are to be given in exchange for any thing but provisions —

J.C.”

Soon after establishing a camp, Cook set out for a look-see, accompanies by Mr Banks and others, leaving thirteen marines and a petty officer to guard the tent.

Cook and his company had not gone far when there was conflict back at the tent. One of the locals took a fancy to one of the petty officers’ muskets and took to purloining it. The midshipman petty officer ordered the marines to fire on the crowd of more than a hundred. After a pursuit the thief was shot dead, but apparently no one else was injured.

Lieutenant Cook was not impressed with the conduct of the petty officer and had to use all of his powers of persuasion in an attempt to calm the locals and proceed with his mission. But he succeeded and later at the fort the transit of the planet Venus across the sun’s disk was observed with great success by Dr. Solander and Mr. Green.

Stage 1 of Lieutenant Cook’s mission had been a success. And now it was time to depart for much greater glory….